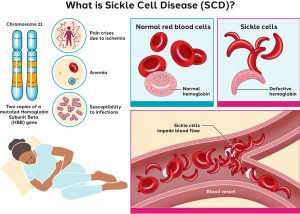

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is an inherited genetic condition that causes red blood cells to assume a rigid, crescent-like shape. These malformed cells obstruct blood vessels, leading to severe pain and life-threatening complications.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported in 2006 that Africa is the epicentre of sickle cell disease globally, with Nigeria alone accounting for an estimated 2 per cent of affected newborns.

According to the Centre for Policy Impact in Global Health, Nigeria bears the highest burden, with approximately 50 million people carrying the sickle cell trait. The centre also reports 150,000 new cases annually.

According to the Centre for Policy Impact in Global Health, Nigeria bears the highest burden, with approximately 50 million people carrying the sickle cell trait. The centre also reports 150,000 new cases annually.

Tragically, nearly half of affected children in Nigeria die before their fifth birthday, while those who survive face a life expectancy of around 21 years. This is generally lower than the 54 years seen in high-income nations.

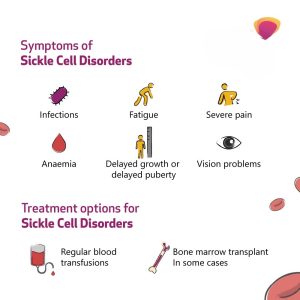

In addition to frequent bone pain crises, SCD brings with it a range of other complications, including stroke, dactylitis (swelling of the hands and feet), anemia, leg ulcers, infections, osteonecrosis, and priapism. In spite of these severe challenges, little has been done to provide the necessary legal framework to alleviate the struggles of those affected.

In 2021, a bill to address sickle cell disease passed its third reading in the Nigerian Senate, but it has since stalled in the Federal House of Representatives. If passed, this bill would offer much-needed legal support for the prevention, control, and management of the disease, potentially reducing early deaths and curbing unnecessary medical expenses.

However, in the absence of such a framework, countless Nigerians continue to face the physical, emotional, and financial burdens of the disease.

Sadly, living with sickle cell disease is an ongoing struggle. For patients like Ms. Peace John, a 24-year-old graduate from the University of Abuja, the daily challenges are often overwhelming.

Currently hospitalised at the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH), Peace speaks about her experiences, saying that the constant crises sometimes leave her with thoughts of death.

Currently hospitalised at the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH), Peace speaks about her experiences, saying that the constant crises sometimes leave her with thoughts of death.

However, her greatest fear is the pain her passing would cause her family, particularly her mother, who has been her primary caregiver.

“I just want to give my mother a good life because she has really tried. She’s always in the hospital with me, she goes through every crisis with me, and I see the pain in her face and voice.

“It’s heartbreaking to watch her get everything the doctors request. I should be the one caring for her, not the other way around”.

Peace also speaks about the challenges of relationships, noting that potential partners often withdraw when they learn of her genotype.

She advocates for greater awareness to dispel the stigma surrounding sickle cell carriers and calls for the term ‘warriors’ to replace the derogatory label ‘sickler’.

Her mother, Mrs. Grace John, expresses a bittersweet mix of joy and sorrow.

She describes her daughter as an angel; kind-hearted, patient, and loving.

According to her, in spite of her pain, Peace’s positive spirit shines through, and her mother continues to hold onto hope for a cure.

“When she’s not having a crisis, she is such a sweet girl, she cares for her siblings, is patient, and loves helping others.

“Even during a crisis, she tries to hide her pain to make the rest of us feel better”.

However, the financial burden is immense, as Mrs. Grace laments the high costs of medications and hospital bills, particularly for blood transfusions.

“The exchange transfusion that my daughter needs now costs 1.5 million naira in private hospitals because most government hospitals either lack the necessary equipment or their machines are faulty.

“Medications are more expensive than before, and getting them has become another problem.

“I believe someday there would be a cure for her condition, so she can live a drug-free life like her siblings and friends,” she said.

She added that the cost of medical care continues to rise, yet it remains a major burden for families battling sickle cell.

She emphasised that government intervention, particularly in subsidising medications and providing financial support, is crucial to easing the strain on affected families.

A haematologist at UATH, who pleaded anonymity, urges strict adherence to medical advice for patients, emphasising that many patients fail to take their medications properly or maintain a healthy lifestyle.

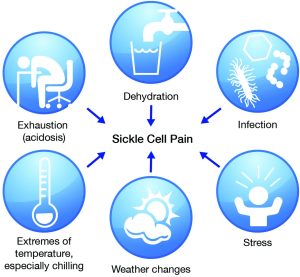

The expert says that dehydration, poor nutrition, and exposure to malaria can exacerbate the crises, saying these factors can be controlled with proper care.

“The medications are expensive, but they are necessary for survival. “Patients need to stay hydrated, eat nutritious meals, and avoid risky environmental conditions to reduce the frequency of crises”.

In response to the growing challenge of sickle cell, numerous advocacy groups, including the Coalition of Sickle Cell NGOs in Nigeria, have called on the Nigerian government to prioritise the passage of the sickle cell bill.

The bill would create a legal framework for disease management, prevention, and treatment.

Ms. Toyin Adesola, Chairperson of the Coalition, urged the National Assembly to expedite the passage of the sickle cell bill, emphasising the importance of public awareness and genotype compatibility before marriage.

“We need to educate people not only about sickle cell but also about how to prevent the condition from being passed down,” Adesola stated.

She explained that such education would help individuals make informed marital choices, thereby reducing the chances of transmitting the sickle cell trait.

“We need to let people know that this is an issue that must be discussed not only now but consistently.

“You cannot ignore the reality of living with sickle cell. People need to understand that while marriage remains a personal choice, it comes with consequences”.

Adesola also called on the National Assembly to revisit the bill and urged the federal government to address the high cost of pharmaceutical drugs for managing the disease.

She warned that without targeted efforts to prevent and manage sickle cell, achieving Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which focuses on good health and well-being, could remain unattainable.

Adesola further recommended widespread campaigns on genotype testing and education on compatibility, particularly in schools, religious centres, and rural communities, to ensure the message reaches a broader audience.

The Nguvu Change Leaders Organisation has also proposed the implementation of laws requiring premarital genotype testing.

They believe this would help prevent marriages between carriers and ultimately reduce the number of sickle cell trait carriers in the population.

As the fight against sickle cell persists, the need for increased awareness, government intervention, and adequate healthcare provisions has never been more urgent.

Many believe that only through collaborative efforts can the struggles of sickle cell patients and their families be alleviated. (NANFeatures)