A Cambridge-led study has shown why many women experience nausea and vomiting during pregnancy — and why some women become so sick they need to be admitted to hospital.

The culprit is a protein known as GDF15 — a hormone produced by the foetus.

But how sick the mother feels depends on a combination of how much of the hormone is produced by the foetus and how much exposure the mother had to this hormone before becoming pregnant.

The discovery, published in Nature, points to a potential way to prevent pregnancy sickness by exposing mothers to GDF15 ahead of pregnancy to build up their resilience.

the baby growing in the womb is producing a hormone at levels the mother is not used to. The more sensitive she is to this hormone, the sicker she will become

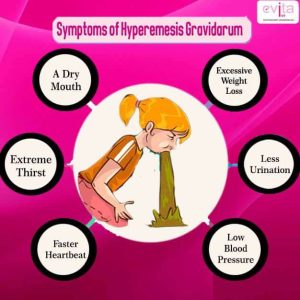

According to researchers, as many as seven in 10 pregnancies are affected by nausea and vomiting. In some women — thought to be between one and three in 100 pregnancies — it can be severe, even threatening the life of the foetus and the mother and requiring intravenous fluid replacement to prevent dangerous levels of dehydration.

Described as hyperemesis gravidarum, scientists say the condition is the commonest cause of admission to hospital of women in the first three months of pregnancy.

Described as hyperemesis gravidarum, scientists say the condition is the commonest cause of admission to hospital of women in the first three months of pregnancy.

Lead researcher, Prof. Stephen O’Rahilly, from the University of Cambridge, says although some therapies exist to treat pregnancy sickness and are at least partially effective, widespread ignorance of the disorder compounded by fear of using medication in pregnancy mean that many women with this condition are inadequately treated.

Until recently, the cause of pregnancy sickness was entirely unknown. Recently, some evidence from biochemical and genetic studies has suggested that it might relate to the production by the placenta of the hormone GDF15, which acts on the mother’s brain to cause her to feel nauseous and vomit.

Now, an international study, involving scientists at the University of Cambridge and researchers in Scotland, the USA and Sri Lanka, has made a major advance in understanding the role of GDF15 in pregnancy sickness, including hyperemesis gravidarum.

The researchers showed that the degree of nausea and vomiting that a woman experiences in pregnancy is directly related to both the amount of GDF15 made by the fetal part of placenta and sent into her bloodstream, and how sensitive she is to the nauseating effect of this hormone.

The researchers showed that the degree of nausea and vomiting that a woman experiences in pregnancy is directly related to both the amount of GDF15 made by the fetal part of placenta and sent into her bloodstream, and how sensitive she is to the nauseating effect of this hormone.

GDF15 is made at low levels in all tissues outside of pregnancy. How sensitive the mother is to the hormone during pregnancy is influenced by how much of it she was exposed to prior to pregnancy — women with normally low levels of GDF15 in blood have a higher risk of developing severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

“We now know why: the baby growing in the womb is producing a hormone at levels the mother is not used to. The more sensitive she is to this hormone, the sicker she will become.

“Knowing this gives us a clue as to how we might prevent this from happening. It also makes us more confident that preventing GDF15 from accessing its highly specific receptor in the mother’s brain will ultimately form the basis for an effective and safe way of treating this disorder,” Prof. O’Rahilly said.