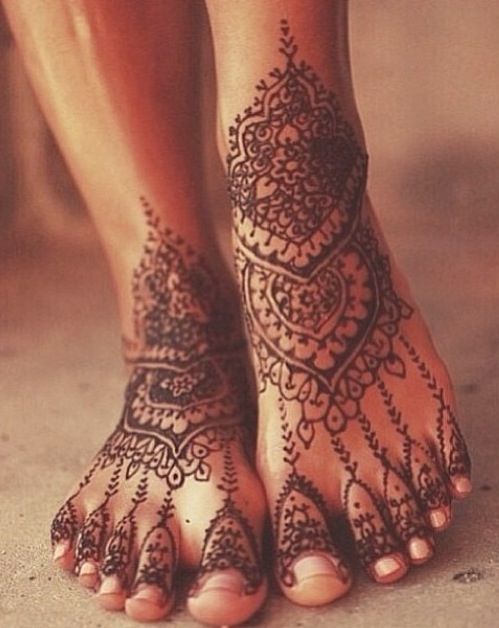

The joyous Eid-ul-Adha, popularly known as Ileya celebration, is here, and one cannot overlook the captivating art form with henna that adorns the hands and feet of many celebrants.

The Yoruba call Eid-ul-Adha, ILEYA (Ile ti ya), meaning ‘It is time to go home’. This simply advised that when it is time for this Sallah, wherever you are, go home.

Henna, scientifically known as Lawsonia inermis, has been used for centuries as a form of temporary body art and natural dye. Its origins can be traced back to ancient civilizations in Egypt, India, and the Middle East.

In Nigeria, henna plays an integral role in various cultural celebrations, including weddings, festivals like Ileya, and other joyous occasions.

Its history in Nigeria is deeply rooted in the country’s rich cultural heritage and traditions. Known as ‘Lalle’ in the Hausa language, henna has been a part of Nigerian culture for centuries, with its usage spanning various regions and ethnic groups.

The exact origin of henna in Nigeria is not well-documented, as the practice predates written records. However, it is believed to have been introduced to the region through cultural exchanges and trade routes with North Africa and the Middle East.

Different ethnic groups in Nigeria have their unique henna traditions and designs, but the Hausa-Fulani community, predominantly in the northern part of Nigeria, has a strong henna tradition.

Different ethnic groups in Nigeria have their unique henna traditions and designs, but the Hausa-Fulani community, predominantly in the northern part of Nigeria, has a strong henna tradition.

The Hausa henna designs are characterised by intricate geometric patterns and motifs, often applied on the hands, feet, and sometimes other parts of the body while the Yoruba community, primarily in the southwestern part of Nigeria embraces henna as a part of their cultural practices.

In Yoruba culture, henna is applied during traditional weddings, where the bride’s hands and feet are adorned with elaborate designs. These designs may incorporate elements inspired by the adire fabric, a traditional Yoruba textile art.

Also, the Kanuri, Igbo, Nupe, and other ethnic groups in Nigeria have their distinct henna traditions and practices, which may vary in terms of designs, techniques, and occasions for application.

Henna is made from the powdered leaves of the henna plant, scientifically known as Lawsonia inermis. The henna plant, which is native to regions of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, are harvested, dried, and ground into fine powder, which is then us

ed to create the henna paste.

To make henna paste, the henna powder is typically mixed with liquid, such as water, lemon juice, or tea, to form a thick, smooth consistency. Other ingredients, such as sugar, essential oils, or herbs, may be added to enhance the texture, fragrance, and color of the paste.

The henna paste is then left to sit for several hours or overnight to allow the dye molecules in the henna to release and create a

stain. Then, the henna paste is ready to be applied to the skin.

Henna transcends mere body art; it is a testament to cultural identity, symbolism, and the beauty of traditions passed down through generations. It has evolved over time, influenced by cultural interactions, contemporary trends, and individual creativity.

A henna and traditional spa specialist, Fatimah Umar Atana, says beauty is part of Islam and that as the ileya festival draws near, every Muslim is expected to beautify his or her self.

“It’s actually a once in a year celebration, so, our scholars advise each one of us to beautify ourselves for that very d

ay. Henna is part of beauty for women only in Islam. It is allowed for young girls and women to have it as long as they are interested.

“Henna beautifies the skin and makes it glow. It also brings lovely and soothing attraction to the eyes when perfectly designed.”

According to Atana, henna is 100 percent made from natural leave; adding that aside being used for skin design, it is also used for several other things such as hair steaming, body polishing, clearing sunburns as well as treatment of wounds. “She noted that it has no side effect once it is 100percent natural.”

She described the henna designers as creative individuals while she encouraged Muslim women and girls to adorn their hands and feet for the ileya celebration. The cost of designing the two hands, she said, is about N1,500 and same amount for designing the feet too.

How safe is henna on skin?

A Dermatologist at Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, Christine Poblete-Lopez, shares a few tips on what users need to know when getting henna tattoos done. She advised users to steer clear of black henna ink or temporary henna that contains ink.

She pointed out that henna, which has been used by different cultures for centuries, is usually brown or orange-brown in colour and it is made from grinding dried henna leaves worked into a paste.

The temporary safe tattoos, according to her, usually last about two weeks until they begin to fade.

“While traditional henna is considered safe to use in temporary tattoos, users must watch out for black henna ink.

“Natural henna takes a few hours to be absorbed into the skin and causes few allergic reactions, according to one study but when other ingredients, such as p-phenylenediamvine (PPD) are added to it, the result is marketed as ‘black henna’, which is often used in the tattoos to help make them darker and longer-lasting,” she explained.

She further made known that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warns that the ink in some temporary tattoos can cause serious allergic reactions that can outlast the tattoo itself.

The reactions include:

- Redness

- Blisters

- Raised red weeping lesions

- Loss of pigmentation

- Increased sensitivity to sunlight

- Permanent scarring.

“Henna tattoos by themselves aren’t necessarily the problem. It’s when they add other components to make them darker or react more quickly, that poses the problem,” Dr. Poblete-Lopez said.