In a medical result released on Thursday by online platform Nature Medicine, malaria resistance and treatment failures can now be reduced by at least 81 percent.

An international research team led by Penn State investigated various drug policy interventions using the Rwanda situation where Artemisinin resistance was first reported in 2020 as a case study.

The report noted that among other strategies, the research team found that next-generation interventions such as triple ACTs (TACTs) – which combine an artemisinin derivative with two partner drugs or which use a sequential course of one ACT formulation, followed by a different ACT formulation – resulted in treatment failure counts that were at least 81% lower.

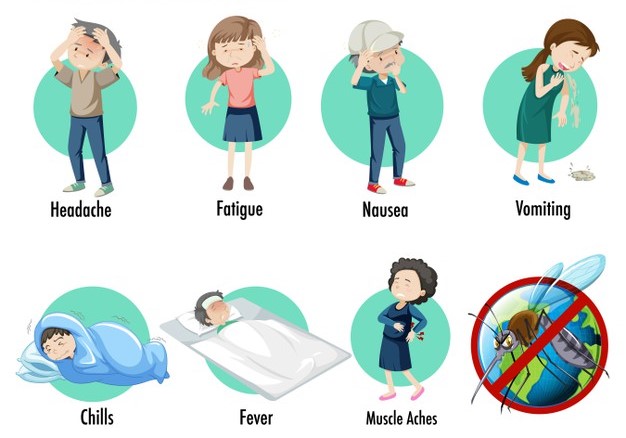

The research team further noted that Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the globally-accepted first-line treatments for malaria — a mosquito-borne disease caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite that annually kills around 600,000 people, mostly children.

Sadly, however, resistance to ACTs by P. falciparum has emerged in recent years in Africa, threatening their effectiveness, the research team noted.

Speaking on the latest result, Robert Zupko, Assistant Research Professor of Biology, Penn State, said, “The malaria drug-resistance situation in Rwanda in particular, is urgent and have the propensity to spread to other countries within the continent. If we let things continue as is, artemisinin-resistant genotypes will begin to dominate by the end of this decade.

“Of the two dozen interventions we evaluated, we found that TACTs — a treatment yet to be approved to treat malaria but undergoing clinical evaluations — was projected to minimize both treatment failures and drug resistance.”

Also, a senior author on the study, Dr. Aline Uwimana, who doubles as the head of case management at the Rwanda Biomedical Center, cautioned that waiting for optimal therapies may not be the best approach as resistance could soon be widespread.

He said, “Of the available and approved approaches that we evaluated for this study, there were several options using multiple first-line (MFT) therapies, that we could begin to put into place next year as this is likely the most feasible choice in the near term for our country and the wider continent.”

Uwimana further noted that under an MFT strategy, multiple therapies are deployed at once and different patients get treated with different drugs.

Another professor of biology at Penn State, Maciej Boni, said the current situation in Rwanda is a repeat or “three-peat” of past malaria drug failures.

In his comments, he noted that since the 1940s, multiple antimalarial drugs have been deployed worldwide, but the eventual development of drug resistance in the malaria parasite forced the withdrawal of all of them.

“In the 1990s, new artemisinin drugs were trialed and found to be effective, and by 2005 they were recommended worldwide, he said.

“The following year, Rwanda adopted the ACT artemether-lumefantrine (AL) as its first-line therapy for malaria, but by 2020, a mutation, known as ‘pfkelch13 R561H’, was shown to have emerged over the previous decade.

It was the R561H mutation that is associated with delayed clearance of the parasite in the presence of AL, he informed.